Viewers of the Fox Television series Sleepy Hollow follow a story very loosely based on one of America’s first hits in the world of literary fiction, penned by the Hudson valley writer Washington Irving. The TV show is set in the Tarrytown, New York area (dismissing by default Kinderhook, New York’s claim to be the setting of Irving’s story). It even has a character named “Frank Irving”, giving a nod to the 19th century originator of this fantasy. The TV show requires enormous suspension of disbelief; mine is always ruined by the Spanish moss draped trees of the show’s shooting locations (and not exactly renewed by the long aerial shots of the lower Hudson estuary shown during scene changes).

Washington Irving’s short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is from an 1820 book named The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. The Sketchbook is a collection of Irving’s stories put together as a marketing strategy meant to undermine the pirating and unauthorized publishing of his individually released stories in England. It also contains a group of stories reporting on a fictionalized Christmas vacation spent in a remote English manor called Bracebridge Hall. Bracebridge Hall is the just the kind of place where ancient Christmas customs (fast-disappearing in a modernizing world) might be expected to survive, or even flourish under the guiding hand of an aged lord of the manor and the eager participation of the younger generations (I count two younger generations and various age-cohorts of children populating the Christmas festivities).

My sense is that Irving (born in 1783, at the end of the American Revolution) was keenly aware of the passing of yesterday’s world and the arrival of a new one. The on-going social tension of this process seems evident in the “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” where a school-teaching ethnic English newcomer, Ichabod Crane, tries to settle into a rural New York Dutch community, only to be challenged by a bully with a long, local bloodline. Irving gives us another take on out-with-the-old, in-with-the-new through “Rip Van Winkle” (also in The Sketchbook), which lets the reader feel how startling it would be to fall asleep in a quiet, Hudson valley corner of the British Empire and awaken 20 years later in the undreamed of American republic. With regard to the Bracebridge Hall Christmas stories, it seem that in a world that had literature and writers but no ethnography, Irving presciently assumes the 19th century ethnographer’s task of rescuing ancient traditions before they could disappear.

This is, however, fiction, neither methodical ethnography nor disciplined folklore. It is what Irving created instead, and admittedly, it is a synthesis of some sort, as if all the reported customs were practiced in the same time and place ca. 1815-1820. In the words of Irving’s alter ego, Geoffrey Crayon:

“At the time of the first publication of this paper the picture of an old fashioned Christmas in the country was pronounced by some as out of date. The author had afterward the opportunity of witnessing almost all the customs above described, existing in unexpected vigor in the skirts of Derbyshire and Yorkshire…”

Irving devoted 5 chapters of The Sketchbook to old English Christmas customs, many of which are still referred to today although not necessarily practiced. The chapter titled “Christmas” is an introduction, and acquaints us with a concept lost today, which is that Christmas, standing close by the winter solstice, is especially tinged with supernatural power. We learn that the all-night crowing of the rooster announced “the sacred festival” while keeping away the power of evil. Irving punctuates these stories with English poetry of an earlier age. The following unattributed verses reporting the beneficial effect of the cock’s crow emphasize the point:

“The nights are wholesome—no planets strike,

No fairy takes, no witch hath power to charm,

So hallowed and so gracious is the time.”

Gracious, meaning full of grace, like “Hail Mary, full of grace”. In the second chapter, “Stagecoach” the growing sense of Christmas cheer is conveyed through a coach ride with young companions anxious to get home for a 6 week vacation from school, their joyful departure as they reach their destination, and the narrator’s stay at a comforting inn before continuing his own journey. The inn’s servants and landlady bustle, guests warm themselves before the fire, hams and other delicacies hang in the kitchen. In this chapter we are blessed with another burst of verse, describing

“A handsome hostess, merry host,

A pot of ale now and a toast,

Tobacco and a good coal fire,

Are things this season doth require.”

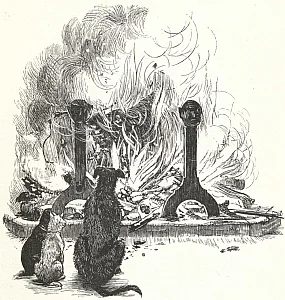

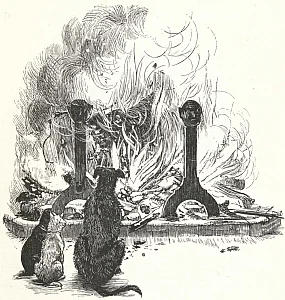

Yule Log. "Old Christmas" from the Sketch Book of Washington Irving illustrated by R. Caldecott.

In the third chapter, “Christmas Eve”, the narrator arrives at Bracebridge Hall under the moonlight, to the barking of dogs. He enters a world in which the old English customs are not only celebrated, but enforced by old Mr. Bracebridge (often referred to as “the squire”). The squire is tolerant enough to allow the introduction of tea and toast to the traditional meat and beer-heavy breakfast (in the next chapter) but not enough to allow singing in French (in this one). On Christmas Eve the yule log (referred to as the “Yule clog”) blazed; this is a custom discussed in some detail. The north of England was the Yule log’s stronghold as customs changed or died out. The yule fire was the scene of “drinking, singing, and telling of tales”. But it could be attended by bad luck if the fire went out during the night, or if a barefoot or squinty-eyed guests arrived.

After the Christmas Eve supper there was singing and dancing. The “Troubador” dissuaded from singing in French offered a song attributed to the 16th-17th century English poet Herrick. It also deals with the familiar Christmas-time theme of warding off spirits and supernatural beings (the first line appears to be a compliment, don’t let it put you off):

“Her eyes the glow-worm lend thee,

The shooting stars attend thee,

And the elves also,

Whose little eyes glow,

Like the sparks of fire, befriend thee.

No Will o’ the Wisp mislight thee,

Nor snake nor slow-worm bite thee,

But on, on the way,

Not making a stay

Since ghost there is none to affright thee.”

After a few more semi-scary verses, the singer delivers his heart-felt message: “Then, Julia, let me woo thee”. And the woman named Julia did everything but notice.

The fourth chapter, “Christmas Day” finds the author awaking to the sound of joyful children on a sunny morning. He attended a religious service where old Mr. Bracebridge exalted the heart with the singing of a carol the old man adapted from a Herrick poem:

“Tis thou that crownst my glittering hearth

With guiltless mirth,

And giv’st me Wassaile bowles to drink

Spiced to the brink…”

For the purpose of the song, these are the words spoken for this occasion by a tenant farmer and Christmas guest to his landlord and host, as celebrated in verse by the landlord and host. The landlord, Mr. Bracebridge, followed the old injunction to feast his neighbors: “At Christmas be merry and thankful withal, and feast thy poor neighbors, the great and the small.” After church, the hall was opened to the neighbors for Christmas festivities, with beer, food, and games.

The fifth and last of these chapters is titled “The Christmas Feast”. Opening verses provide vivid imagery “Lo, now is come our joyful feast! Let every man be jolly, Each room with yvie leaves is drest, And every post with holly”. They also evoke the Christmas spirit:

Without the door let sorrow lie,

And if, for cold, it hap to die,

Wee’le bury ‘t in a Christmas pye,

And evermore be merry.”

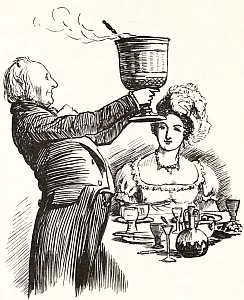

The Squire's Toast. "Old Christmas" from the Sketch Book of Washington Irving illustrated by R. Caldecott.

The traditional delicacies of the Christmas feast include a boar’s head and peacock (although in this story peacock is not served as the year had been hard on the peacocks). Serving the boar’s head, replete with its own Christmas carol, is an old custom the squire had preserved at home (it reminded him fondly of his college days). Wassail was served as well. We learn that wassail could be made from ale instead of wine; that it might be spiced with a variety of things including nutmeg, ginger, sugar, toast, and roasted crabs; and at one time it was served in a bowl passed between the drinkers, although by the writer’s era it was drunk from individual cups.

After dinner a considerable period of drinking and story-telling ensued, perhaps to the extent of infringing upon wakefulness and sobriety. Not to worry, though: the manor house was about to explode with mirth and romping, as one particular adult, gone into character as the Lord of Misrule, led a ragged tag-like game for children clothed in customs designed from the garments of the manor family’s ancestors, dragged out of storage for the occasion.

What did Washington Irving intend his readers to believe about this? He tells us by saying “…these fleeting customs were posting fast into oblivion, and that this was, perhaps, the only family in England in which the whole of them was still punctiliously observed.”

And for the satisfaction of readers who don’t think history is very important, what was the point of telling this Christmas story? For the pleasure of reading it, the author asserts, in case it will “in these days of evil, rub out one wrinkle from the brow of care, or beguile the heavy heart of one moment of sorrow”. The point is to make the reader “more in good humor.” And so these stories come recommended. Merry Christmas!