I set aside the book I was reading and noticed the bramble and rosebush scratches on my arm. They made me think about my recent experiences on Phase 1 archaeological surveys in Hudson Valley thickets from Fishkill to Saratoga Springs.

I looked at the book’s cover. Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann. It’s the story of how suddenly oil-rich Osage Indians were being killed by devious white people to gain hold of their fortunes, and how the nascent FBI battled through corruption to investigate these murders. Knowing I would quickly finish this amazing book, I got up and went into the library to look for the next one to read.

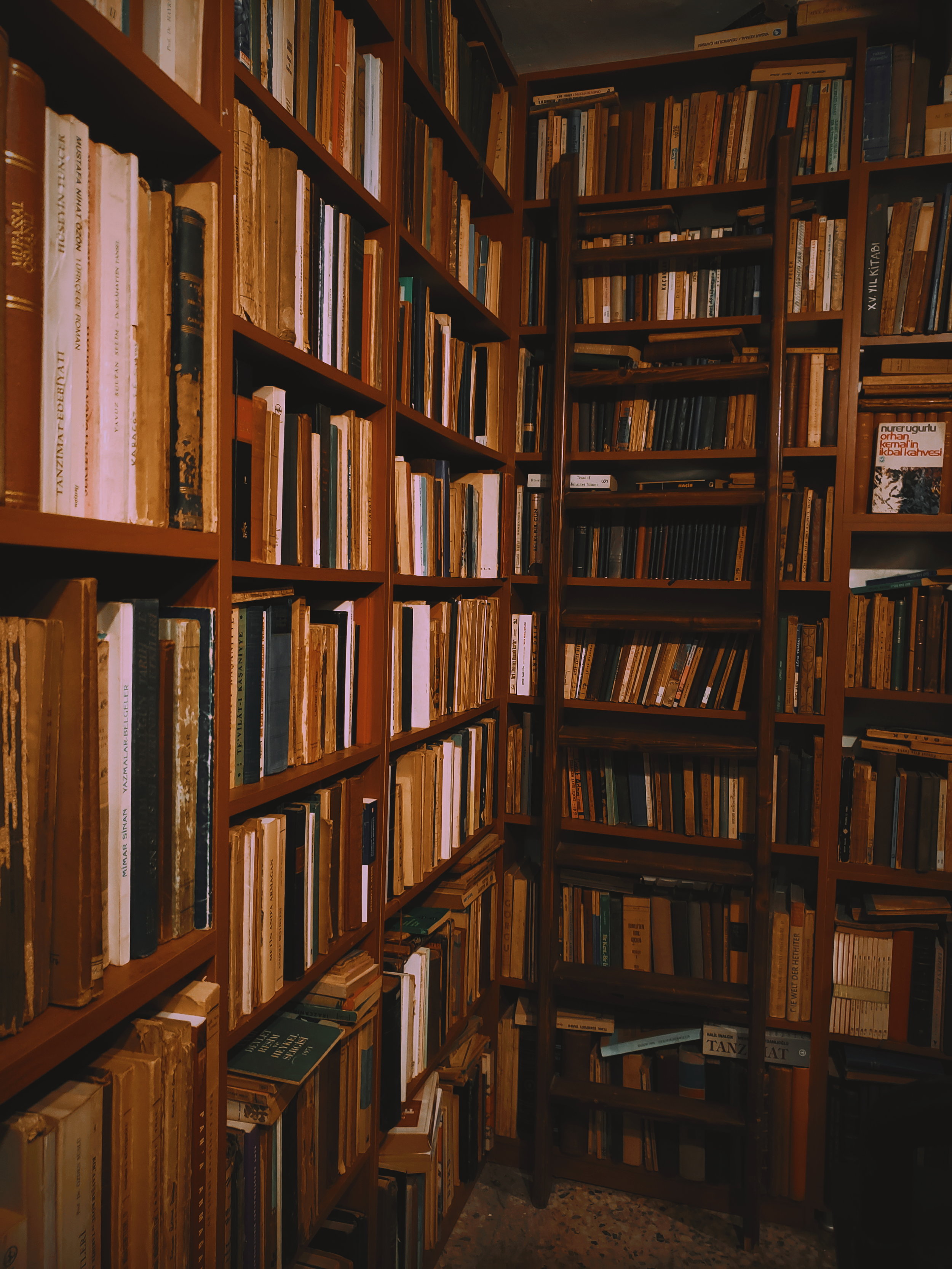

I entered the dark, east end of the library. This side of the room has no windows, just bookshelves, crates of vinyl records, stereo equipment, and a couple of lamps and chairs. Several shelves away, however, the west end opens into a small, bright solarium, three sides lined with large windows and a variety of indoor plants: begonias, Swedish ivy, lemon geraniums, Christmas cacti and others. The library is a nice place. In fact, it feels like two nice places.

Scanning the volume titles on the shelves, I pulled out David Crosby’s autobiography, then put it back. A lot of water has gone under the bridge since he wrote that. There were a few books from my childhood and teen years on the next shelf. Bomba the Jungle Boy in the Swamp of Death (copyright 1929). That’s from my grandmother’s house. I read it over and over as a kid, as decades before me others had as well. It immediately reminded me of my work-a-day jungles and swamps, of struggling through the brush, the heat, the muck, the ticks. Then I found another book from Grandma’s house: The Wind Wagon, a book about a boy transported back in time, traveling through ancient lands in a flying chariot (with no horses: it had pinwheels that made it fly on its own). The Wind Wagon was a good companion for a boy who liked Greek and Roman mythology.

The old books section. Nearby on the same shelf I spied Mark Twain’s Letters from the Earth. I bought this paperback in a drugstore when I was in high school in Geneva, New York. Not the drugstore I worked in, where the druggist, Clarkie, had a novelty stoneware crock labeled “OPIUM” on the floor of his work area. It resided next to his right foot. The stoneware was too thick to break if Clarkie kicked it by accident. A jar labeled “OPIUM” probably started as pharmacist humor but was a fairly good joke all-around in Geneva ca. 1969. No, I found Letters from the Earth in the more modern drugstore across town. People interested in writing should take a look at this book, if for no other reason than it contains Twain’s essay “Cooper’s Prose Style” (sometimes referred to as James Fenimore Cooper’s “literary offenses”). In Letters from the Earth, Twain’s sharp pen found many victims to alternately lampoon or condemn. Evolutionists will like “Was the world made for man?” while students of cultural relativism could welcome “The French and the Comanches” into the canon of Anthropology forerunners. Or if you want to learn what was left out of the Book of Genesis, read “Papers of the Adam Family.”

In my book-collecting life, I have acquired some abridged but still very thick volumes. One is the abridged version of Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. I saw it on a shelf in my library with other books on ancient and medieval history. There it sat next to The Farfarers by Farley Mowat (The Farfarers! One of these days I will have to write a stand-alone review of this very original vision of North Atlantic history).

I thumbed through The Decline and Fall. Such a compelling title. Friends, Romans, and Countrymen, are we in a spiral of decline and fall? Should I contemplate Gibbons’ history in terms of our present-day predicament? My thumb found the part about how the first emperor, Augustus, was able to grow his unprecedented power with ease because the Roman Senate was very accommodating to him. Hmmm.

I didn’t get very far into The Decline and Fall before I put it down, took a chair, and browsed through a much slimmer page-turner, The Day of the Barbarians by Alessandro Barbero. Not surprisingly, after that glimpse of The Decline and Fall, I was more than a little aware of possible ancient parallels with today. In the fall of AD 376 the Goths, who dwelt across the Danube from the Roman Empire, suddenly became refugees from Hun invaders pressing upon their lands from the east. Although the Romans allowed the Goths to cross the Danube and tried to settle them within the empire (continuing a longer relationship, as Rome had welcomed earlier Goth immigrants into its military), two years dragged by, Roman corruption reigned, the Goths went hungry, resettlement faltered, public opposition to resettling the Goths increased, and war broke out, frustrated and desperate Goths against the powerful Roman army. There is a glaring historical difference from the present-day situation as refugee immigrants to America are not an armed force capable of threatening the US military. So a historical lesson in this case involves the realization that widespread fear of the other now is unwarranted given the kinds of refugee issues we have.

Getting back to the Roman case, however, the Goths defeated the Roman army and killed the emperor, Valens, in AD 378 (Yes, unlike American Commanders-in-Chief, Roman emperors led their troops in battle and occasionally gave their lives to the cause). How the Romans reacted to the news of catastrophic defeat in this infamous Battle of Adrianople illustrates misinformation spreading through political factions within a great nation. Again, it is problematic to see close parallels with our social-political world, but it is interesting to note that the spread of inaccurate information was indeed an issue in that ancient time and functioned as propaganda to promote the interests of factions.

In those days, the government controlled accurate information about what was happening. Little of it was released to the public. Most of what people thought they knew was based upon rumors and urban legends that spread from person to person and community to community. For example, the body of Valens was never found and although many thought it was left on the battlefield (which is most likely), an alternative and politically charged narrative soon was in the air. This alternative is the story that Valens perished in a burning farmhouse. It seems fair at this point to emphasize the contrast between the competing narratives of an emperor who died leading his troops and one who died sheltering in a farmhouse. The rumor spread across the eastern empire until unruly mobs in far-away Antioch began to shout the slogan “Let Valens burn alive!”

More broadly, interpretations of Valens’ death and the loss of the war to the Goths diverged among the Roman Empire’s major competing religious factions. There were three of these in the late fourth century: Catholics, Arian Christians, and pagans. The Catholics circulated a story that a holy monk, Isaac, had warned Emperor Valens (who was an Arian) to restore the primacy of the Catholics or he would be destroyed. Valens, according to the story, had Isaac arrested and went off to fight the battle. Following the obvious implication, the Catholic interpretation of the Roman defeat and Valens’ demise was that God had exerted his will in favor of the Catholics as Isaac had prophesied. What the Arians thought is unknown because with the subsequent rise of the Catholics, the Arian writings were destroyed. However, it is worth noting that the Goths were Arians as well as victors in their rebellion against the Romans, and we can judge that their interpretation may also have been that their victory was God’s will, regardless of the Catholic reason for holding this view. A prominent pagan position, which has survived in the words of the Sophist teacher Libanius, seems to be that the Roman generals and soldiers deserve credit and honor for their bravery, but their defeat was due to the pagan gods becoming angry with Rome. Angry for reasons perhaps all too obvious to pagans who were fading into the background during the fourth century rise of Christianity. But all of these are inaccurate, self-serving stories amplified by demagogic orators. The reason that the Goths defeated the Romans is purely military. The rest was fuel for fourth century political infernos.

I looked at my phone to check the time. It was getting late. It was time to make a decision about what to read next. I slipped Day of the Barbarians back into its slot on the bookshelf and pulled out the similarly slim volume next to it: Ivory Vikings by Nancy Marie Brown. A quick look showed that this is the reconstructed, plausible story of a talented female artist in twelfth century Iceland who may have carved the Lewis Chessmen, some of the most iconic images of Norse men and women (even including berserkers biting their shields). The Lewis Chessmen were found centuries later on the Scottish Isle of Lewis (where Brown’s thesis may be just a little controversial). This book also is about the Viking trade in walrus ivory. Some recent scholarship relates the collapse of the walrus ivory market in Europe to the collapse of the medieval Norse colony in Greenland. Very exciting! And a bit mysterious. A perfect choice to start the winter’s reading.